Smart solutions? A look back at technology in dementia care’

Benson, S. (2025) ‘Smart solutions? A look back at technology in dementia care’. Journal of Dementia Care, 33(6) pp. 44-48

Sue Benson sifts through JDC archives that remind us of huge changes in the world of technology, in all our lives as well as dementia care, since 1993.

When the Journal of Dementia Care (JDC) began in 1993, technology and communications were a world away from the ease and speed of contact and access to information we have now. We communicated through land-line phone calls, fax and post. To look something up we had reference books and directories, the local library, and for journalists, a phone call to the Daily Telegraph Information Service. Email and the internet had begun but were not used widely until many years later. Mobile phones were expensive toys for top executives.

Technology and the senses

The first JDC articles to mention technology of any kind covered multi-sensory environments – remember Snoezelen? The equipment – soft lighting, soothing sounds, fibreoptic light tubes to handle, gently moving projections on to walls – had been found beneficial in care of people with learning disabilities. The whole multi-sensory room concept was strongly marketed but expensive, and sensitive practitioners like Lesley Pinkney at Kings Park Community Hospital, Bournemouth (Benson, 1994) found that simpler means of providing a relaxing environment, perhaps including an item of Snoezelen kit, could be just as effective. The approach remained useful and research in 1997 compared Snoezelen with a one-to-one activity session in a care home and a hospital ward. It found significant and lasting improvement in socially disturbed behaviour in the Snoezelen group (“less shouting, swearing, being objectionable to others”) (Dowling et al.,1997)

Monitoring, safety and security

Mentions of technology for monitoring, safety and security came first in advertising, with competing display ads for nurse call systems. Many of these systems were hard-wired but Radio Nurse Call, for example, promised “easy to fit, no-wiring installation” in 1994.

Key points

- Technology in everyday life has developed beyond recognition from 1993 to the present.

- The first mentions of tech in JDC were descriptions and evaluation of multisensory environments and equipment.

- Practitioners were wary of ‘tagging’ and surveillance systems; ethics and practicalities were discussed in JDC and at our conferences.

- ‘Smart’ demonstration houses were developed to show the potential of different technologies, for both practitioners and people living with dementia and family carers to experience and help develop.

- Different forms of technology to promote relaxation, occupation and fun have been described in JDC over many years

Author Details

Sue Benson was Editor of the Journal of Dementia Care from its first issue in 1993 up until 2012, and has been Managing Editor since then.

The Tabs mobility monitor, a wired system comprising a floor mat with a sensor to alert when someone gets up from a bed or chair, was advertised in 1995. The advert said the system “reduces the need to use either chemical or physical restraints – reducing risk of falls”.

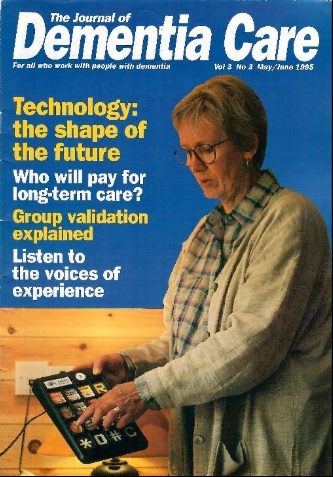

Monitoring technology was widely treated with suspicion at the time, but Professor Mary Marshall, director of the Dementia Services Development Centre, University of Stirling, led a significant shift in attitude. Professor Marshall was closely involved with JDC as an advisor, and in 1995 she wrote: “Two years ago, like most people in the field of dementia care, I would have said that technology had no role to play. My experience was that people with dementia cannot work alarm systems and I was very antipathetic to the tagging and surveillance devices.

“A visit to Finland changed my mind. Anja Lepo in the Department of National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health convinced me that I was behaving like an ostrich. Technology is part of a triangle of care: staff, buildings and technology. This is the shape of the future whether we like it or not, so rather than ignore it we need to know more about it and influence developments.”

In the article she described the kind of tech she saw demonstrated there, and her thoughts on its usefulness(Marshall, 1995). All these threads have been developed in the years since. They included:

- Reminding: A board by the front door to indicate if the cooker was still on or any windows left open.

- Stimulation: Computer software being developed, using ‘hypermedia’, combining text, speech, music, sound effects, drawings, photos and video, to stimulate and refresh the mind.

- Relaxation: The Snoezelen equipment mentioned above, and relaxing videos.

- Compensating: Covering memory lapses, for example a device to stop bathwater overflowing, or to turn off a cooker if an empty pan is left on. The telephone device shown on the cover of the same issue (pictured on the previous page) has photographs of people whose number can be called by pressing the image. (In practice this kind of device has proved a mixed blessing, if it leads to constant phone calls to family members.)

- Surveillance technology: including ‘tagging’ devices, videos and passive alarms. Marshall notes that these can be helpfully tuned to individual needs – for example alarms that only trigger after someone has been out of bed for a certain time.

- Communication: she notes the potential of new ‘video telephones’, and the interesting fact that recent books by people with dementia were written using word processors after the authors had lost the skill of handwriting.

Marshall goes on to discuss important ethical issues, including: who benefits? It ought to be the person with dementia but in many cases it will be the carer, staff, or manager. That doesn’t mean tech can’t be used but, she writes, the question “should always be asked and answered honestly”. Consent is another very complex issue discussed in detail here, and this discussion is still relevant to decisions made about technology today.

New approaches; developing technology

In an article the following year Professor Marshall described new approaches she’d encountered (Marshall, 1996). These included passive infra-red devices to record movement, linked to a computer that “knew” whether this was a normal pattern for the person, or not (she saw these in use in Australia). She described a smart house in Brussels, where almost every aspect of living is programmed or operated by a remote control linked to a computer. The front cover of that issue (above) shows a cartoon with a very cynical view of the future of technology in care.

In the same issue is an article by Mark Wrigglesworth of WanderGuard UK, arguing that “Electronic tagging devices are not a restraint but a means of alerting staff to a potential risk situation. Where they are used on the basis of individually assessed risk they are a means to freedom within safe boundaries.” (Wrigglesworth, 1996). At the time the whole issue of “tagging” was very contentious; it had strong associations with prisoners. Now that so many of us have mobile phones and actively want to keep track of family, this issue feels very different.

A 2008 article (Kerr et al., 2008) reporting on research into night-time care practices in care homes revealed a lot of disturbed sleep due to checking activity. It made me think of the improved technological solutions we have now, developed by companies like Sensio and Ally Cares.

Assistive technology

A lot of work involving many organisations led up to the publication in summer 2000 of the ASTRID guide (ASTRID: A Social and Technological Response to meeting the needs of Individuals with Dementia and their carers) and our article (ASTRID, 2000) summarised the guide. In included examples of what was now generally called ‘assistive technology’ in practice, including:

A magnet on the front door to alert a call centre and a neighbour if a vulnerable person leaves the house at night; a timing device to turn off a cooker ring after 10mins; a touchscreen device that played favourite songs or simple memory games; and an automated clock-calendar.

The SMART home

In the same issue is a description of “The house that JAD built”– an example of appropriate design and technology in action. This “Dementia Friendly House” was built as part of the Glasgow ’99 Just Another Disability (JAD) project (Pollock et al., 2000). It included all the kinds of alarms and warning systems mentioned above, and adaptations to compensate for difficulties that come with ageing, not just dementia, such as level access to safe outdoor space and controls that are easier to handle.

Smart home projects proliferated in these years. One example, developed in Gloucester, was described by Andrew Chapman (2001) with some of its technology, including a bath monitor, a night-time toilet guide and a cooker monitor, explained by Roger Orpwood. These articles launched a regular Technology column in JDC reporting on developments. There seemed such a lot of momentum and potential in those years, but how much of it has developed into devices and adaptations actually available to many people living with dementia in the community who could benefit?

Practical steps

From 2000 to 2010 JDC ran an annual one-day conference dedicated to Technology in Dementia Care, where both practical and ethical issues were the topic of lively debate. Jane Gilliard’s 2001 article listed practical steps, identified as important in recent projects discussed at that year’s conference:

- Early identification to enable informed consent and early installation of wiring and equipment.

- A suitable assessment tool is needed, plus thorough care planning, simplified funding, and regular review of the equipment both to check its functioning and assess if it is still meeting a need.

The ENABLE Project

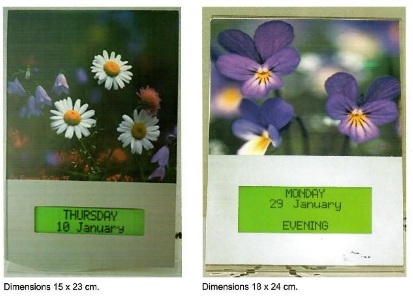

In the following year Inger Hagen and an international team of colleagues reported on the ENABLE project, It brought together experts from Norway, Finland, Ireland and the UK to assess the role of assistive technology in helping people with dementia with everyday activities, and develop new devices (Hagen et al., 2002). They specifically evaluated:

- an automatic day and night calendar (Forget-me-Not)

- a locator for lost devices

- an automatic lamp that turns on when a person gets out of bed

- a bath water level monitor and controller

- a cooker usage monitor

- a remote day planner (this was a screen that displays tasks and activities, information provided by the carer through the internet)

- ‘Picturegramophone’ – favourite music and songs accessed by touching a screen connected to a PC.

This list is a good example of what was available then, and being evaluated in such projects as the Northamptonshire Safe at Home scheme (Woolham & Frisby, 2002) which found that used well this kind of tech was extremely cost-effective. Costs of caring over the six months of the trial increased by around 4% for the for the Safe at Home group and 46% for the control group, largely due to the number of people admitted to residential and nursing homes from the control group.

Change and progress

Practice was slow to change despite the proven benefits. Later in 2002 Mary Marshall wrote an article asking, “Why is technology so rarely a part of care plans for people with dementia? Are technophobic staff discriminating against them?” (Marshall, 2002) Among other possible barriers she listed concern about lack of human contact, but observed that “good practice integrates technology into care practice and extends their potential to help people with dementia stay at home longer.”

Now that so many of us are very happy with technology in everyday life, that attitude has changed dramatically, and some new technologies have been readily adopted. Recent articles in JDC have described how staff use of phone and tablets in care planning, communicating with each other and managers, and finding individual resources to share with individuals – based on personal preferences and local interest.

In 2004 I reported from our latest technology conference that a lot of progress had been made (Benson, 2004). This included a policy drive and government funds, assistive technology being integrated into new buildings, continuing sophistication of the new generation of alarm systems and – for the future – trials of the use of mobile phones to promote independence for those who enjoy walking.

In 2005 Trent Dementia Services Development Centre announced that together with partners it was developing a web-based resource about assistive technology (AT) consisting of “up to date, user-friendly information on AT for people with dementia” (Burrow, 2005) and this was maintained for several years.

In 2005 Fiona Taylor reported on her research into care managers’ views on assistive technology. Her conclusions were mixed: on the one hand there was good evidence of improved service delivery in terms of ensuring less intrusive practice, reducing risks and enabling staff to respond when they are required, but when they asked care managers how often is the person being supported in leaving the house, the answer was “Rarely” (Taylor, 2005).

In 2010 Gill Windle reviewed evidence for the entire spread of telecare provision and its potential to contribute to quality of life and well-being for people with dementia. She concluded that the potential was great, but there was a need for more robust research, especially to hear views of users of the services and care provider organisations about the strategies, operation and personal factors that impact on telecare provision.

Technology to detect health problems – such as urinary tract infections (UTIs) – in people with dementia living at home proved very successful in a pioneering study involving Surrey University and Surrey and Borders Partnership NHS Trust and others (Rostill, 2019). The Technology Integrated Health Management described here dramatically reduced visits to A&E and hospitalisation.

Focus on wellbeing and co-production

The Independent Project (Investigating Enabling Environments for People with Dementia) (Chalfont & Gibson, 2006a) was led by a consortium involving primary care (University of Liverpool), architecture (University of Sheffield) and the Bath Institute of Medical Engineering. It focused on “developing technology for enjoyment and wellbeing of people with dementia while integrating it into the living environment in ways that ensure successful and sustainable use.” One example analysed was how to help someone continue their lifetime love of knitting, and there was mention of (at working prototype stage) a simple music playing device operated by just one button. In a second article (Chalfont & Gibson, 2006b) they reported on what factors influence whether a new piece of technology is accepted by people with dementia, emphasising a user-led approach “that involves people living with dementia and their carers in all aspects of the project’s research, design and implementation.”

At our tech conference in 2009 Arlene Astell and Maria Parsons described their experience of piloting and evaluating CIRCA in long-term care settings. CIRCA was a multimedia touchscreen computer system containing a database of photographs, video clips and music to form the basis of activity sessions, one-to-one or in groups. Since then we’ve reported on many examples of using the vast resources of the internet in reminiscence, where searches can find very specific material to match individual interests and histories. Also the potential of virtual reality was emerging, described by Dan Cole, producer of The Wayback VR experience, developed and tested in a care home – in which residents experienced a coronation street party from June 1953 through special headsets (Cole, 2019) . Participants preferred these simple cardboard viewers to watching on a smart phone smart phone, because they felt familiar, “like binoculars or a 1970s slide viewer”.

At one of our tech conferences I remember being very taken with a kitten that “paddled” its paws (widely available as a children’s toy) – I far preferred it to the PARO robotic seal that came later. The PARO seal appeared around 2017; it was designed to be relaxing and calming, but met with a mixed response. It also sparked debate about hygiene when its use was proposed in hospital wards (Martyn & Rowson. 2018).

More successful was the HUG – one of the playful objects designed in the LAUGH Project (pictured on the front cover above). It was the result of a care staff member’s observation that what one profoundly withdrawn resident needed most of all was a hug. HUG contains electronics simulating a beating heart and can play favourite music. It had a strikingly positive effect on this resident and on many others since. The LAUGH project produced other playful objects, some using technology, including one that plays birdsong and changes colour. (Treadaway, 2018). An evaluation of the HUG, reported in Treadaway et al.,(2020) showed many beneficial effects. As well as bringing comfort, it seemed to stimulate people to greater awareness of others around them, and thus alleviate loneliness.

Future potential

All the threads mentioned above have continued to develop in sophistication, and new themes and concerns are emerging.

From 2020 onwards, the Covid pandemic gave a boost to online communication and meeting over distance, including support groups and video-based support for carers (eg Chatwin et al., 2020).

Digital diagnostic (and self-diagnostic) tests are flourishing, as are digital games to stimulate cognition and games to increase awareness of dementia (eg one aimed at young people, described by Mitchell (2021). Digital technology can help to predict deterioration in frail older people, described by Anita Astle (2023).

Artificial Intelligence was first discussed in JDC in an article by Thomas Sawyer of Cognetivity, describing its potential in diagnosing dementia (Sawyer, 2019). Since then we’ve had discussion of its potential, if well used, to aid care planning and record-keeping (Elkins, 2025). This is one of many areas of technology now developing at breakneck speed. JDC will aim to explain and discuss them all in the months and years ahead.

References

All references are from the Journal of Dementia Care (JDC).

Astle, A. (2023) ‘Digital technology as a tool for predicting deterioration in frail older people: A case study’, JDC, 31(6), pp, 29-30.

ASTRID (2000) ‘ASTRID: introducing assistive technology’, JDC, 8(4), pp. 18-19.

Benson, S. (1994) ‘Sniff and doze therapy’, JDC, 2(1), pp. 12-14.

Benson, S. (2004) ‘State of the AT’, JDC, 12(6), p. 5.

Burros, S. (2005) ‘Technology resource’, JDC, 13(4), p. 17.

Chalfont, G., and Gibson, G., (2006a) ‘How assistive technology can improve wellbeing’, JDC, 14(2), pp. 19-21

Chalfont, G., and Gibson, G. (2006b) ‘Putting technology to work for quality of life’, JDC, 14(3), pp. 30-31.

Chapman, A. (2001) ‘There’s no place like a smart home’, JDC, 9(1), pp. 28-31.

Chatwin, J., Yates Hoyles R., and McEvoy, P. (2020) ‘Video-based support service for carers’, JDC, 28(2) pp. 12-13.

Cole, D. (2019) ‘The Wayback: an immersive virtual reality experience’, JDC, 27(4), pp. 16-17.

Dowling, Z., Baker, R., Wareing, L.A., and Assey, J. (1997) ‘Lights, sound and special effects?’, JDC, 5(1), pp. 16-18.

Elkins, Z. (2025) ‘The AI revolution: what does it mean for dementia care?’, JDC, 33(2), pp. 12-13.

Gilliard, J. (2001) ‘Technology in practice: issues and implications’, JDC, 9(6), 18-19.

Hagen I., et al (2002) ‘A systematic assessment of assistive technology’, JDC, 10(1), 26-28.

Kerr D., Wilkinson, H., Cunningham, C. (2008) ‘Supporting older people in care homes at night’, JDC, 16(4), pp. 35-38.

Marshall, M. (1995) ‘Technology is the shape of the future’, JDC, 3(3), pp. 12-14.

Marshall, M. (1996) ‘Into the future: a smart move for dementia care?’ JDC, 4(6), pp. 12-13.

Marshall, M. (2002) ‘Technology and technophobia’, JDC, 10(5), pp. 14-15.

Martyn, K., Rowson, C. (2018) ‘The Paro seal: weighing up the infection risks’, JDC, 26(3), 32-33.

Mitchell, G. (2021) ‘Gaming for awareness’, JDC, 29(1), pp. 16-17.

Pollock, R., Bonner, S., Gibbons, K. (2000) ‘This is the house that JAD built’, JDC, 8(4), pp. 20-22.

Rostill, H. (2019) ‘Technology helps people stay healthy at home’, JDC, 27(1), pp. 26-28.

Sawyer, T. (2019) ‘The future of technology in dementia detection and care’, JDC, 27(3), pp. 12-13.

Taylor, F. (20065) ‘Care managers’ views on assistive technology’, JDC. 13(5), pp. 32-35.

Treadaway, C. (2018) ‘LAUGH: playful objects in advanced dementia care’, JDC, 26(4), 24-26.

Treadaway, C., Pool, J., Johnson, A. (2020) ‘Sometimes a HUG is all you need’, JDC, 28(6), pp. 32-34.

Windle, G. (2010) ‘Does telecare contribute to quality of life and well-being for people with dementia?’ JDC. 18(5), pp. 33-36.

Woolham, J., Frisby, B. (2002) ‘How technology can help people feel safe at home’, JDC, 10(2), pp. 27-29.

Wrigglesworth, M., (1996) ‘Time for a fair assessment of the options’, JDC,

4(6), pp. 14-15.