De-Notes

By Toby Williamson

Williamson, T. (2025) De-Notes. Journal of Dementia Care 33(6) pp.51-53

Co-creating films involving people with dementia experiences from biggerhouse film

While planning this special issue of the Journal I had the pleasure of speaking with Stephen Clarke from biggerhouse film, who have made a number of films involving people with dementia connected with the DEEP network and Innovations in Dementia. These include the Okehampton Memory Cafe and the ENLIVEN Advisory Group in Exeter.

Biggerhouse film are a not-for-profit, community interest company (CIC). As well as making films involving people with dementia they also make films with people who are neurodiverse or have learning differences. Stephen used the phrase, “people removed from the centre of the conversation”, and he and his colleagues aim to use film to “give a voice to people who don’t have it”.

The conversation I had with Stephen partly focused on what it was like to make films involving people with dementia, from a film-maker’s perspective. Our conversation went into some of the fine detail of the interactions that can occur in this process, but especially focused on the notion of co-creating films with people with dementia and some of the things involved, including some of the challenges.

Before film-making Stephen’s background had been in participatory theatre and education. He also has his own lived experience of mental health issues. This underpinned his commitment to trying to co-create every part of a film, from the initial idea, what the film showed, and the editing and production processes.

Stephen made the point that as a film-maker he has the privilege (and challenge) of getting very close, very quickly into the lives of people with dementia. But to co-create meaningfully, this also meant allowing the film to go in different directions, with spontaneity, depending on the people he was working with. This could be playful, but also emotional, involving laughter and tears. The film-maker therefore has to strike a balance between their own curiosity and ensuring an appropriate degree of emotional safety for others involved.

Film-making using a co-creation process was therefore a very “delicate” process, to ensure the voice of people with dementia was made “robust”, and they felt that the films showed their “best selves”. Co-editing poses further challenges which Stephen is keen to explore in the future. Stephen also used words such as “poetic” and “beautiful” to describe the experience of film-making, and the joy it can bring in terms of helping build relationships and communities.

As Stephen put it in his film-making approach with people, “let’s sit side by side looking at something, and out of chaos, comes creativity.” He believes this approach increases the profile and awareness of people with dementia, and is determined to develop it further: “say it louder and say it again”. Good luck – we need more of this kind of film-making.

Priorities in policy and practice

The Alzheimer’s Society annual conference is always an important event for gauging current priorities in policy and practice, at both a national level and for the Alzheimer’s Society itself. This year’s conference, in mid-September, was slightly unusual because the Society had not announced the name of its new chief executive officer, following the departure of Kate Lee earlier this year. The new CEO was announced two weeks after the conference. Her name is Michelle Dyson; she had been Director General of Social Care for the last four years at the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), and a civil servant for a number of years before that.

The focus of the conference was on health inequalities and dementia (as a priority for the Society this may of course change over time, with a new CEO taking charge). It has to be said that it’s been known for a number of years that health inequalities seriously affect the risk and prevalence of dementia, diagnosis rates, access to services, and experiences of care and support. However, as long as inequalities remain an issue, it’s important to draw attention to them.

The conference heard from Stephen Kinnock MP, Minister of State at DHSC, with responsibilities for dementia (his mother was diagnosed with dementia in 2017, and died in 2023).

The Government had recently announced that as part of the new 10-Year Plan for the NHS there would be a ‘Modern Service Framework for Dementia and Frailty’ (MSF). The Minister described this as a “radical plan” but didn’t give much detail other than wanting to improve diagnosis rates. Diagnosis rates had also been referred to by other speakers, who had talked about a new plan for dementia as a ‘once in a generation opportunity’. It made me feel slightly old and cynical, having lived through three national plans for dementia in England between 2009 and 2016 (not to mention plans elsewhere in the UK), all of which were a lot more ambitious than just trying to improve diagnosis rates. Remember ‘dementia friendly communities’? As a rudimentary form of the social model of disability they were radical, but there was no mention of them by the conference speakers.

There were lots of good contributions from people living with dementia, family carers, service examples, projects and interesting research. I’m hoping that the Journal will feature some of this in the future.

One example was the findings from the DETERMIND study which showed that late diagnosis of dementia did not only affect people from minority ethnic communities and people of lower socio-economic status. Late diagnosis also affected more affluent white people living in rural areas, perhaps because of factors such as access to services, stigma, and fear of losing a driving licence and therefore becoming cut off and isolated.

There were some moving films about music therapy from the charity supporting this work, Nordoff and Robbins, and a presentation reporting on the good work being done by the Northern Care Alliance (an NHS trust in Greater Manchester) to improve hospital discharge rates for people with dementia. The Bristol Dementia Wellbeing Service talked about how they were engaging with male carers from the Chinese community. It was also really helpful to have a session where organisations working with other health conditions (diabetes, cardiovascular, and Parkinson’s) talked about how they had addressed health inequalities.

It struck me towards the end of the conference that if organisations are serious about addressing health inequalities in dementia, the MSF for dementia and frailty referred to by Stephen Kinnock, might be one way of doing this. So too would a rights-based approach to dementia policy – maybe the MSF could use this as a guiding principle.

Museums: a flourishing legacy

I also recently attended the ‘Dementia, Museums and Wellbeing’ conference at the Wallace Collection, a national museum in central London with a fine collection of paintings, sculpture, domestic items, arms and armour.

In the early days of the ‘dementia friendly’ community movement in England, back in 2012, I would never have guessed that making museums dementia accessible would be a flourishing legacy of that movement. But the Dementia Friendly Heritage Network, hosted by the Historic Royal Palaces, has over 80 members, and has held national conferences, of which this was one. The Network has numerous well-known national museums, galleries and heritage sites as members, including the Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales – seven national museums of Wales.

It was so encouraging to hear all the initiatives that are going on in the museum and heritage sector for people affected by dementia. Heritage should be an enjoyable experience for people with dementia (and family carers) to engage with. But it can also be cognitively stimulating, provide opportunities to reminisce and connect personal stories with stories and artefacts contained in museums and other historical sites. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London, has hosted a cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) project for people with dementia.

What was also very positive to hear was how museums and collections had responded to issues of inclusion and diversity. For example, following a carefully thought-out process of engagement, people from the Caribbean Social Forum based in south London had been influential in reshaping some of the displays at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

There were too many other good presentations to describe, but the use of the national sound archive at the British Library as a way to enable people with dementia to reminisce, including on the topic of Sunday lunches, was very enjoyable.

The conference gave me further impetus to try and get an arts and heritage project off the ground for people with dementia and family carers, involving a Grade 2 listed, 19th century mansion near to where I live in south London. The building is called Kingswood House and was largely built by a Scotsman, John Lawson Johnston, who invented the liquidised beef drink, Bovril (the House has the nickname of ‘Bovril Castle’). The House was also owned by a family who supplied beef from cattle ranches they owned abroad, so as a vegetarian, that aspect of the House isn’t the most pleasant for me! However, it may be a good hook for the project we are planning; I’m not sure when it will happen, but trusting that it does, I will tell you all about it in a future issue.

Sad farewells

Ron Coleman

I was very sad to hear the recent news of Ron Coleman’s death. We plan to include an obituary from someone who knew Ron well through the work Ron did as someone living with dementia in the next issue of the Journal, but I wanted to say a few words of my own.

Although very sad, it seems fitting to be writing about Ron in this special issue of the Journal as I got the impression he was a great user of tech. For example, he contributed a number of entries to Dementia Diaries. Ron was also a real activist, vocal, forthright and passionate in his views, even where these could make for uncomfortable listening. I had a great respect for him because of that but I didn’t find it difficult to discuss these with him, even if there was a difference of opinion.

I also had an admiration for Ron because I had known of him from the late 1990s when I worked in the field of mental health, focusing on “functional” mental health problems, such as schizophrenia. Ron had been diagnosed with schizophrenia as a result of hearing voices (“auditory hallucinations”). Ron wrote extensively about how his experience of different psychiatric treatments based on this diagnosis were counter-therapeutic and disempowering, having been compulsorily detained in hospital under the Mental Health Act on numerous occasions. It was only when he became involved with the Hearing Voices Network (HVN) that he understood these unpleasant voices not to be symptoms of an illness but connected with abuse he had experienced as a boy. HVN’s approach was a key element in Ron’s recovery. He subsequently developed voices groups with HVN, published books about recovery using the HVN approach, and ran recovery training courses and events (with his partner Karen Taylor).

All of that may not seem very relevant to the world of dementia. But my awareness of HVN meant that when I co-ordinated the Dementia Truth Inquiry involving people with dementia who experienced different realities I was able to get a speaker from HVN to talk to the inquiry. Even better, we also heard from a psychiatric nurse, David Storm, who leads work in Cumbria using the HVN approach for people with dementia (Supporting people living with dementia who hear voices).

So thank you Ron, although it is very sad you are no longer with us, you have left an important legacy.

The condolences of everyone here at Dementia Community go out to Ron’s wife Karen, and his family and friends.

Prunella Scales

Another loss worth noting is that of the actor, Prunella Scales. I can’t claim that I ever met her and my only knowledge of her was based on seeing her on TV. In her later years she and her husband, Timothy West (who died last year) made a series of programmes documenting their journeys on canal boats in the UK and further afield (Great Canal Journeys). All ten series they appeared in were made after Prunella Scales was diagnosed with vascular dementia in 2014.

The couple openly discussed living their lives in the context of Prunella’s dementia. The intention of the discussions didn’t seem to be particularly focused on awareness-raising or for educational purposes but was more personal. Of course, one always has to be cautious about how truthful TV programmes really are, but what I thought was very positive was the way Prunella appeared to be living fairly well with dementia, and the strong emotional bond between her and her husband. Prunella was able and active in boating duties, and after mooring up at the end of the day, they always seemed to enjoy a glass or two of wine. Dementia was certainly a feature in their lives, and a challenge at times, but the portrayal was balanced and sympathetic, without over-dramatising, stigmatising or showing Prunella in a negative light. Honest, humane and respectful. Decent TV.

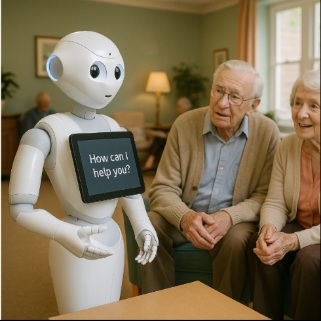

Pepper the robot

I never met, let alone owned a ‘Pepper’ robot, but I was a bit sad when I heard that its manufacture had stopped in 2021. Pepper is (was?) a ‘semi-humanoid’ robot that’s about four foot tall with a touch screen on its chest. It was designed not to carry out domestic tasks but to help people to enjoy life, connect with the outside world, and have fun. There’s an entertaining short film about Pepper here – I particularly liked Pepper’s challenge to play a game involving holding one’s breath, and Pepper’s air guitar moves. Costing around £1,500, there were 27,000 Peppers made before manufacturing stopped.

Pepper was designed to read emotions based on detection and analysis of facial expressions and voice tones. Beyond what it says on Wikipedia and the manufacturers website I don’t know much about Pepper. However, I guess it was designed before AI and machine learning, so it had limited responses, and these weren’t personalised to the individual it was interacting with. This left me wondering whether a version of Pepper that could acquire more and more learning about an individual; their life story, relationships, likes and dislikes, beliefs and interests, and so on, could become a “proper” companion for someone with dementia. In theory, Pepper would never get tired of the person, or express impatience with repeat questioning. It could discuss with ever-growing knowledge the performance of the person’s favourite football team, recipes, the latest episode of Traitors, or world news, what their grown-up children were doing, or express understanding and sympathy when the person was upset.

As discussed elsewhere in this issue of the Journal, there are lots of ethical issues arising from modern technology being used in dementia care. Were a robot like Pepper to acquire more and more personal information about someone, issues of data privacy obviously arise. And of course there’s the whole question of replacing humans with humanoids, which frequently generates very negative responses. And what about people who couldn’t afford a robot companion?

But with so many voice-activated devices around and AI being so ubiquitous, it’s hard not to see robot companions becoming more and more common. Furthermore, an increasing number of people are growing old alone, including an estimated 120,000 people in the UK with dementia. I imagine that for some people with dementia, a humanoid companion would be a welcome alternative to having no-one to talk to. So, RIP Pepper. Perhaps ‘Capsicum’, your time may come.